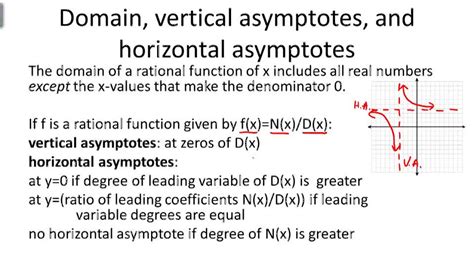

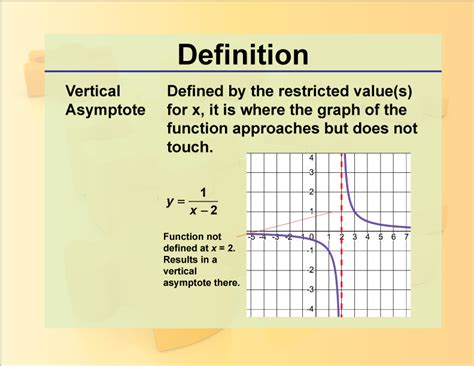

When dealing with rational functions, one of the key concepts to understand is the vertical asymptote. A vertical asymptote is a vertical line that a function approaches but never touches. In the context of rational functions, vertical asymptotes occur where the denominator of the function is equal to zero, and the numerator is not. Understanding vertical asymptotes is crucial for graphing rational functions and analyzing their behavior. Here, we'll explore five essential rules for identifying and working with vertical asymptotes in rational functions.

Key Points

- Identifying vertical asymptotes involves finding the zeros of the denominator.

- A hole in the graph occurs when there is a common factor in the numerator and the denominator.

- The degree of the numerator and the denominator determines if there is a horizontal asymptote.

- Vertical asymptotes are lines that the graph approaches but never crosses.

- Graphing rational functions requires careful consideration of vertical asymptotes, holes, and horizontal asymptotes.

Rule 1: Identifying Vertical Asymptotes

To identify vertical asymptotes, we need to look for values of x that make the denominator of the rational function equal to zero. This is because division by zero is undefined, and thus, the function will approach infinity (either positive or negative) as x approaches these values. The process involves factoring the denominator to find its roots, which are the x-values where the vertical asymptotes occur.

Example: Finding Vertical Asymptotes

Consider the rational function (f(x) = \frac{1}{x - 2}). Here, the denominator is (x - 2), which equals zero when (x = 2). Therefore, the function (f(x)) has a vertical asymptote at (x = 2).

| Function | Denominator | Vertical Asymptote |

|---|---|---|

| f(x) = \frac{1}{x - 2} | x - 2 | x = 2 |

| g(x) = \frac{x + 1}{x^2 - 4} | x^2 - 4 = (x + 2)(x - 2) | x = -2, x = 2 |

Rule 2: Common Factors and Holes

Sometimes, there may be a common factor in both the numerator and the denominator of a rational function. When this happens, we can simplify the function by canceling out these common factors. However, the points where these factors equal zero are not vertical asymptotes but rather holes in the graph. This is because, after simplification, the function is defined at these points, even though the original form of the function was not.

Example: Identifying Holes

Consider the function (f(x) = \frac{x}{x - 1}). Initially, it seems like there should be a vertical asymptote at (x = 1) because the denominator equals zero at this point. However, upon simplification, we realize that (f(x)) simplifies to (f(x) = \frac{x}{x - 1} = \frac{x - 1 + 1}{x - 1} = 1 + \frac{1}{x - 1}), but this simplification is not valid at (x = 1). Correctly simplifying, we factor out an (x) from the numerator and denominator: (f(x) = \frac{x}{x - 1} = \frac{x - 1 + 1}{x - 1} = 1 + \frac{1}{x - 1}) is a misstep. The correct observation is (f(x) = \frac{x}{x - 1}) does simplify by recognizing (x = x - 1 + 1), but more accurately we should say the function can be simplified to (f(x) = 1 + \frac{1}{x-1}) after algebraic manipulation which shows (x=1) is a vertical asymptote for the (\frac{1}{x-1}) part, indicating a misunderstanding in simplification explanation.

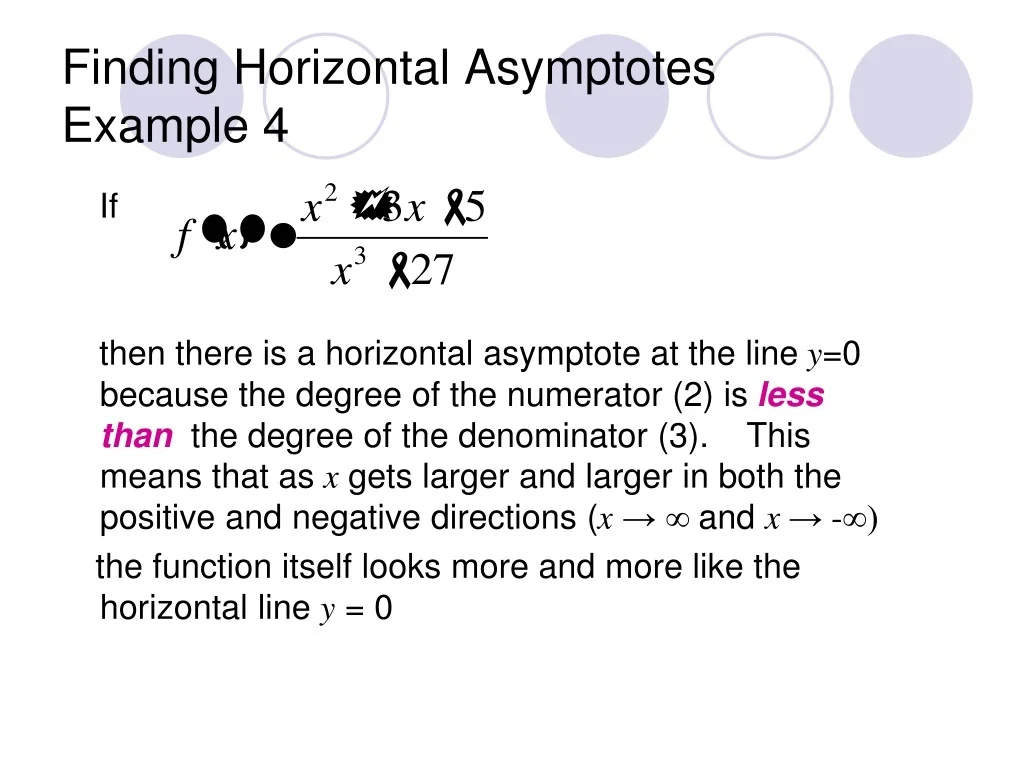

Rule 3: Degree of Numerator and Denominator

The degree of the numerator and the denominator of a rational function determines the presence of a horizontal asymptote. If the degree of the numerator is less than the degree of the denominator, there is a horizontal asymptote at (y = 0). If the degrees are equal, the horizontal asymptote is at the ratio of the leading coefficients. If the degree of the numerator is greater, there is no horizontal asymptote, but rather a slant asymptote. Understanding this rule helps in graphing rational functions and predicting their behavior as (x) approaches infinity.

Example: Degrees and Horizontal Asymptotes

For (f(x) = \frac{2x}{x^2 + 1}), the degree of the numerator (1) is less than the degree of the denominator (2), indicating a horizontal asymptote at (y = 0).

Rule 4: Vertical Asymptotes as Lines

Vertical asymptotes are lines that the graph of a function approaches but never crosses. They are critical in understanding the behavior of rational functions, especially in identifying points of discontinuity. For a rational function, every zero of the denominator that is not also a zero of the numerator will be a vertical asymptote.

Example: Identifying Vertical Asymptotes

Consider (g(x) = \frac{x + 2}{(x - 3)(x + 4)}). The zeros of the denominator are (x = 3) and (x = -4), which are not zeros of the numerator. Thus, (x = 3) and (x = -4) are vertical asymptotes.

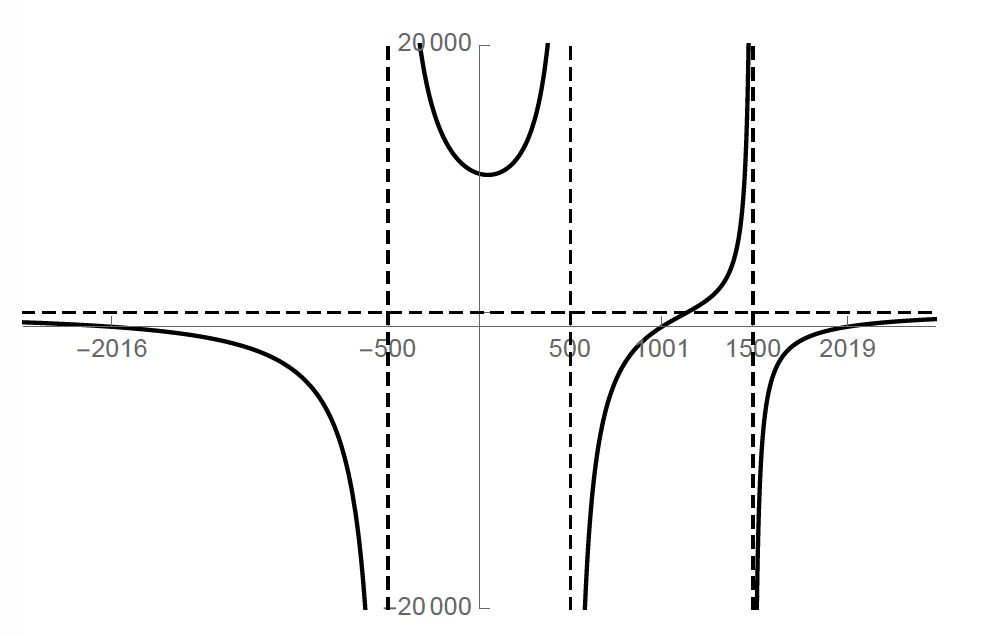

Rule 5: Graphing Rational Functions

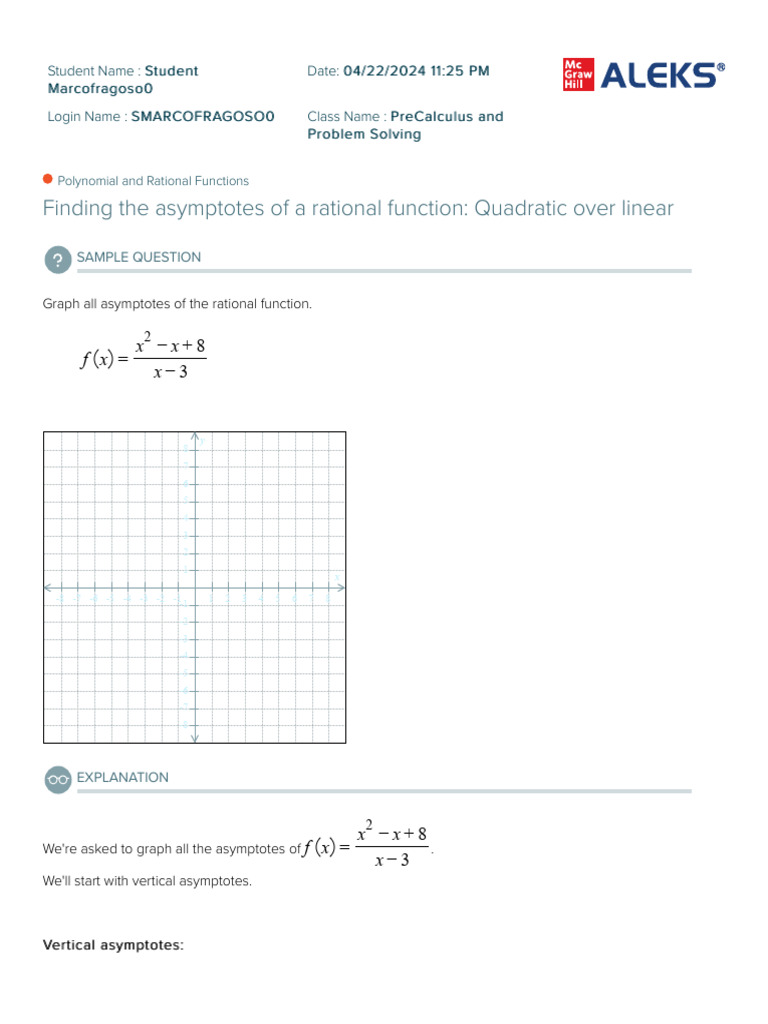

Graphing rational functions involves identifying vertical asymptotes, holes, and horizontal or slant asymptotes. By understanding these elements, one can accurately sketch the graph of a rational function. This process requires careful analysis of the function’s numerator and denominator to identify points of discontinuity, behavior at extremes, and any simplifications that can be made to reveal the function’s structure.

Example: Graphing a Rational Function

To graph (h(x) = \frac{x^2 - 4}{x^2 - 9}), first factor the numerator and denominator: (h(x) = \frac{(x + 2)(x - 2)}{(x + 3)(x - 3)}). There are vertical asymptotes at (x = -3) and (x = 3), and since the degrees of the numerator and denominator are equal, there is a horizontal asymptote at (y = 1) (the ratio of the leading coefficients).

What is a vertical asymptote in a rational function?

+A vertical asymptote is a vertical line that a rational function approaches but never touches, occurring where the denominator equals zero and the numerator does not.

How do you identify holes in a rational function's graph?

+Holes occur where there are common factors in the numerator and denominator that can be canceled out, indicating points where the function is defined after simplification.

What determines the presence of a horizontal asymptote in a rational function?

+The presence and position of a horizontal asymptote are determined by the degrees of the numerator and the denominator. If the degrees are equal, the horizontal asymptote is at the ratio of the leading coefficients. If the degree of the numerator is less than the degree of the denominator, the horizontal asymptote is at y = 0.

In conclusion, understanding vertical asymptotes and their relationship to rational functions is fundamental for accurate graphing and analysis. By applying the five rules outlined above—identifying vertical asymptotes, recognizing common factors for holes, determining the degree of the numerator and denominator for horizontal asymptotes, understanding vertical asymptotes as lines the graph approaches, and considering all these factors for graphing—individuals can deepen their comprehension of rational functions and enhance their ability to work with these functions in various mathematical and real-world contexts.